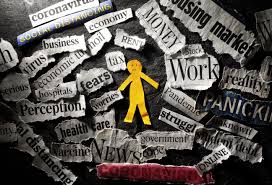

In a world focused on how to handle this pandemic and just past the World Mental Health Day, I'd like to highlight the impact of the current situation on people who need mental health support, with a specific focus on autistic people because of my work as a researcher in the autism field.

Europe counts over 6 million cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) with almost 232,000 related deaths. One of the greatest risks during this pandemic is the overwhelming and sustained demand for healthcare resources, which may exceed the capacity of healthcare systems, leading to unadequate help and increase of deaths. To reduce pressures on health and social care systems, almost all countries have implemented mitigation measures aimed at reducing transmission of the virus among people, including national lockdown policies that might be either very strict (like in Italy) or so-called smart (like in the Netherlands). These measures seem to have worked properly at reducing infection rates before the Summer, nevertheless the benefits were rather slow to see and many countries experienced demands that far exceeded available resources on testing capacity, personal protective equipment and hospital/ intensive care capacity even months after the implementation of those measures. This leads notable concerns for the current increase in cases and what looks like a second hit of the virus. In this crisis, people with mental health conditions, like autism, may be particularly vulnerable to being excluded from services, proper support and treatment, as already reported by recent studies from the US.

People with autism have a higher risk of developing severe illness for COVID-19 because of the frequent presence of physical health conditions like asthma, diabetes, obesity or other immune conditions, nevertheless they might still experience inequalities in access to COVID-19 services. They were and are, in fact, often excluded due to selection policies in healthcare that built on pre-existing barriers experienced by patients with autism like communication difficulties (for instance describing pains and symptoms), reduced involvement in healthcare decision-making by healthcare providers, sensory sensitivities (for instance around physical examinations but also difficulties in tolerating swab procedures for testing), and limited knowledge about autism among professionals treating COVID-19. Furthermore, prevention measures and ICU triage protocols often do not take into account additional needs from people with autism or similar conditions, and so they directly or indirectly discriminate against those people. For instance, people with autism might have difficulty in maintaining physical distance, might not understand why they need to wear a mask and even resist wearing one or attempt to remove the mask of their caregivers, and might show reduced compliance for oxygen or respiratory support. The environment in emergency departments is also not optimal for people with autism, especially children. Waiting rooms can be, in fact, overwhelming especially during peak times, as well as the pace and intensity can be very distressing.

In addition to limitations in access to treatment, we must consider how these people experienced an abrupt interruption to social care services, like community-based services, behavioural therapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy, as well as special educational programmes for children. This profound disruption to routines caused extreme emotional and behavioural distress in people with autism, who are obsessed with routines, and considerable challenge to their caregivers. Not to mention the profound emotional distress caused by the separation of individuals with autism from their families, or caregivers, in case of infection from the virus. Taken all this together, individuals with autism and their parents or caregivers might find themselves anxious and frustrated. In particular, working from home or having lost their job, like many unfortunately, but also with reduced professional and social support, families with an autistic child experience higher pandemic-related stress compared to those without.

We must also consider the positive notes in this crisis as in the efforts from many services and individual professionals to adapt to these exceptional times and keep up with their work and support autistic people. Examples of such innovative and positive solutions are online toolkits to support families or expert webinars on coping with uncertainty, but also telehealth interventions prove to be very useful in autism given the high affinity of autistic individuals for tech. Similarly, governments have also undertaken positive actions through adaptations to national policies during lockdown or similar, like exceptions on wearing face masks in public and allowing increased daily exercise.

In conclusion, it is clear that we are all facing unprecedented difficulties in this COVID-19 pandemic and must take all care of mental health alongside safety for ourselves and others. But it is particularly necessary to integrate mitigation measures against further spread of the virus with best possible measures to reduce inequalities and support people with mental health conditions like autism. Luckily enough, we are building up experience after months in this pandemic and governments, with support from research and clinical work in the mental health field, are implementing better strategies to allow proper accessibility to testing and treatment, adaptation of protocols and continuation of health and social care in this second wave of the virus.

Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Jones N, Cannon M, Correll CU, Byrne L, Carr S, Chen EYH, Gorwood P, Johnson S, Kärkkäinen H, Krystal JH, Lee J, Lieberman J, López-Jaramillo C, Männikkö M, Phillips MR, Uchida H, Vieta E, Vita A, Arango C. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Sep;7(9):813-824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32682460; PMCID: PMC7365642.

Eshraghi AA, Li C, Alessandri M, Messinger DS, Eshraghi RS, Mittal R, Armstrong FD. COVID-19: overcoming the challenges faced by individuals with autism and their families. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7(6):481-483. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30197-8. Epub 2020 May 20. PMID: 32445682; PMCID: PMC7239613.

Pellicano E, Stears M. The hidden inequalities of COVID-19. Autism. 2020 Aug;24(6):1309-1310. doi: 10.1177/1362361320927590. Epub 2020 May 18. PMID: 32423232.

Yahya AS, Khawaja S. Supporting Patients With Autism During COVID-19. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020 Jul 2;22(4):20com02668. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20com02668. PMID: 32628369.

Narzisi A. Handle the Autism Spectrum Condition During Coronavirus (COVID-19) Stay At Home period: Ten Tips for Helping Parents and Caregivers of Young Children. Brain Sci. 2020 Apr 1;10(4):207. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10040207. PMID: 32244776; PMCID: PMC7226467.

Nollace L, Cravero C, Abbou A, Mazda-Walter B, Bleibtreu A, Pereirra N, Sainte-Marie M, Cohen D, Giannitelli M. Autism and COVID-19: A Case Series in a Neurodevelopmental Unit. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 11;9(9):E2937. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092937. PMID: 32932951.

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Comments

Post a Comment